The "Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith" chapter researched and written by Emma Eckert and Bob Eckert from the 2010 book, "Rio Arriba: A New Mexico County," complied and edited by Robert J. Torrez and Robert Trapp

Cattle being driven along NM 96 toward Coyote, New Mexico. They are being moved to higher pastures to afford better grazing in the National Forest.

In 2009 I was contacted by Robert Torrez and Robert Trapp to research and write a chapter for their upcoming book “Rio Arriba: A New Mexico County,” which was subsequently published by Rio Grande Books in 2010. As some of the research needed was to be done at the University of New Mexico, and my oldest daughter was living in Albuquerque, I decided to share the work of research and writing with her. The following is our chapter titled “Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith.” Although these four communities are located in northwest New Mexico, I feel the information is relevant in terms of small villages and towns throughout New Mexico. I’ve added some images from the area to offer some idea of the geography and lifestyles involved. The photos shown here are not included in the book although there are some photos used that the editors chose for publication.

This is one of the first edits and is longer than the actual chapter in the book, but I feel that some of the information that was edited out (for reasons of space) provides interesting insights into this area of Northern New Mexico, so I have included it here.

Story by Emma and Bob Eckert

Photos by Bob Eckert

Overview

Along Highway 96, there is a scenic stretch of road, traveling amongst diverse landscapes. Passing from the man made beauty of the Abiquiú Dam, into the high desert plains, arroyos carving out deep gashes in the earth below flat-topped mesas. A beautiful expanse of sky resting comfortably on the mountains covered with ponderosa, and red sandstone formations are abundant. Tiny rivers run through the valleys, with alfalfa fields green against the red earth. Orchards bearing apples, cherries, and apricots, with the grass growing green and tall, and horses running through fields alongside the irrigation ditches. Great sand stone cliffs butt up against jagged expanses of rocks upturned on their sides, layer upon layer of geologic history exposed in the road cuts made by the highway department. Old adobe houses sit alongside aluminum sided singlewides. In the section of Rio Arriba County that is home to villages like Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith, here is where you can find some of the friendliest, most generous people. Rich with the knowledge of the history of their ancestors and the land that they grew up on, the residents are a veritable fountain of knowledge. Some may be so old that they have trouble conveying their expertise, and others may have moved away, drawn to the more tumultuous life of the larger cities, but the importance of passing the history along remains. Grandmothers teach their grandchildren how make tortillas or apple pies, using the wood stove in their kitchen and speaking only in Spanish. In an instant, this land can make you lose your sense of time, feeling transported back to a simpler era, where the heritage is valued, and the asparagus grows wild along the acequia.

Youngsville

Eighteen miles west of Abiquiú, nestled between the scenic, tree-covered mountains of the National Forest and low, sagebrush dotted plains, in the shadow of the majestic Cerro Pedernal, lies the village of Youngsville. Home to a little over one hundred residents, like most rural Northern New Mexican towns, Youngsville strives to maintain a strong sense of culture and tradition. Originally known as Plaza de los Encinos, or Rito de los Encinos, depending on the source, the village began in the early 1800’s, settled by sheep and goat herding farmers from nearby Abiquiú, Cañones and the upper Rio Chama. The initial residents moved into the area in the first decade of the 19th century. Living in fortified mud villas, the adobe walls were intended to keep out raiding natives, who were taking refuge in the mountains surrounding the area. These settlers ran sheep and goats, and grew meager gardens to sustain themselves. Due to increased raids by natives during the first half of the 1800’s, those living in Rito de los Encinos and surrounding villas were forced by necessity to move back to Abiquiú or Santa Cruz de la Canada for safety.

American frontiersmen, with the repeating Winchester rifles they carried, came and drove the natives west, effectively opening the land back up. Feeling more secure, residents could return to the area they or their compadres had built upon earlier. Soon they returned to the way of life as known before, herding in the mountains in the summer, and wintering in the lower elevations. Prior to the start of the 20th century, Rito de los Encinos was largely undeveloped. In 1913, Jack Young began a Pony Express-like mail service, in addition to opening a general store. It was at this time that Mr. Young changed Rito de los Encinos to Youngsville. Sheep provided the economic basis, enabling their herders to trade wool for goods, bartering for coffee or sugar at Youngsville’s general store or selling the wool to wagons in Abiquiú headed for California.

In the early 1920’s, major changes began happening for Youngsville residents. The Federal Government had an order to take over land of those who didn’t have holding claims on their land: the government now managed any land that was not homesteaded, or fenced. Thus began the Forest Service involvement, and along with it came the regulations and permits required to utilize the once communal land. In the 1940’s, the Forest Service began to encourage resident herders to keep cattle instead of sheep, citing the damage sheep caused by eating too much vegetation. Cattle, they claimed, were more adapted to the environment and would cause less damage, eat less vegetation, and trample the land less. This brought about the end to herding sheep, goats, and wild horses that had sustained the population for decades. Families like the Salazars, with thousands of heads of sheep, now had to keep cattle. The cattle industry continued on for years, helping residents survive, but has since died down considerably. Ranching, according to Eddie Salazar of Youngsville, has all but died off. He speaks of only a sparse few families that rely solely on ranching for income or food. Ranching is more of a hobby to him now, Salazar says. It is more of a way to keep tradition and culture alive. Working the land, and passing on the tradition- it is something that has to be done.

There are few jobs in Youngsville, what with the dwindling of the cattle industry and tiny population. You can work with the Forest Service, the schools, the Highway department, or you can commute to the larger towns of Española , Los Alamos and Santa Fe. With the exodus of most of the young people to the larger cities, towns like Youngsville are a dying breed.

We have to pay attention to the history, Salazar says, speaking of the importance of listening to the oral history of older relatives and residents. Driving through the village, and seeing the closed down bar, the abandoned corrals, the ruins of the original settlement, and the non-existent general store, there is a stark reminder that the history is here, but those who can recount it for you may not be.

This is one of the first edits and is longer than the actual chapter in the book, but I feel that some of the information that was edited out (for reasons of space) provides interesting insights into this area of Northern New Mexico, so I have included it here.

Story by Emma and Bob Eckert

Photos by Bob Eckert

Overview

Along Highway 96, there is a scenic stretch of road, traveling amongst diverse landscapes. Passing from the man made beauty of the Abiquiú Dam, into the high desert plains, arroyos carving out deep gashes in the earth below flat-topped mesas. A beautiful expanse of sky resting comfortably on the mountains covered with ponderosa, and red sandstone formations are abundant. Tiny rivers run through the valleys, with alfalfa fields green against the red earth. Orchards bearing apples, cherries, and apricots, with the grass growing green and tall, and horses running through fields alongside the irrigation ditches. Great sand stone cliffs butt up against jagged expanses of rocks upturned on their sides, layer upon layer of geologic history exposed in the road cuts made by the highway department. Old adobe houses sit alongside aluminum sided singlewides. In the section of Rio Arriba County that is home to villages like Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith, here is where you can find some of the friendliest, most generous people. Rich with the knowledge of the history of their ancestors and the land that they grew up on, the residents are a veritable fountain of knowledge. Some may be so old that they have trouble conveying their expertise, and others may have moved away, drawn to the more tumultuous life of the larger cities, but the importance of passing the history along remains. Grandmothers teach their grandchildren how make tortillas or apple pies, using the wood stove in their kitchen and speaking only in Spanish. In an instant, this land can make you lose your sense of time, feeling transported back to a simpler era, where the heritage is valued, and the asparagus grows wild along the acequia.

Youngsville

Eighteen miles west of Abiquiú, nestled between the scenic, tree-covered mountains of the National Forest and low, sagebrush dotted plains, in the shadow of the majestic Cerro Pedernal, lies the village of Youngsville. Home to a little over one hundred residents, like most rural Northern New Mexican towns, Youngsville strives to maintain a strong sense of culture and tradition. Originally known as Plaza de los Encinos, or Rito de los Encinos, depending on the source, the village began in the early 1800’s, settled by sheep and goat herding farmers from nearby Abiquiú, Cañones and the upper Rio Chama. The initial residents moved into the area in the first decade of the 19th century. Living in fortified mud villas, the adobe walls were intended to keep out raiding natives, who were taking refuge in the mountains surrounding the area. These settlers ran sheep and goats, and grew meager gardens to sustain themselves. Due to increased raids by natives during the first half of the 1800’s, those living in Rito de los Encinos and surrounding villas were forced by necessity to move back to Abiquiú or Santa Cruz de la Canada for safety.

American frontiersmen, with the repeating Winchester rifles they carried, came and drove the natives west, effectively opening the land back up. Feeling more secure, residents could return to the area they or their compadres had built upon earlier. Soon they returned to the way of life as known before, herding in the mountains in the summer, and wintering in the lower elevations. Prior to the start of the 20th century, Rito de los Encinos was largely undeveloped. In 1913, Jack Young began a Pony Express-like mail service, in addition to opening a general store. It was at this time that Mr. Young changed Rito de los Encinos to Youngsville. Sheep provided the economic basis, enabling their herders to trade wool for goods, bartering for coffee or sugar at Youngsville’s general store or selling the wool to wagons in Abiquiú headed for California.

In the early 1920’s, major changes began happening for Youngsville residents. The Federal Government had an order to take over land of those who didn’t have holding claims on their land: the government now managed any land that was not homesteaded, or fenced. Thus began the Forest Service involvement, and along with it came the regulations and permits required to utilize the once communal land. In the 1940’s, the Forest Service began to encourage resident herders to keep cattle instead of sheep, citing the damage sheep caused by eating too much vegetation. Cattle, they claimed, were more adapted to the environment and would cause less damage, eat less vegetation, and trample the land less. This brought about the end to herding sheep, goats, and wild horses that had sustained the population for decades. Families like the Salazars, with thousands of heads of sheep, now had to keep cattle. The cattle industry continued on for years, helping residents survive, but has since died down considerably. Ranching, according to Eddie Salazar of Youngsville, has all but died off. He speaks of only a sparse few families that rely solely on ranching for income or food. Ranching is more of a hobby to him now, Salazar says. It is more of a way to keep tradition and culture alive. Working the land, and passing on the tradition- it is something that has to be done.

There are few jobs in Youngsville, what with the dwindling of the cattle industry and tiny population. You can work with the Forest Service, the schools, the Highway department, or you can commute to the larger towns of Española , Los Alamos and Santa Fe. With the exodus of most of the young people to the larger cities, towns like Youngsville are a dying breed.

We have to pay attention to the history, Salazar says, speaking of the importance of listening to the oral history of older relatives and residents. Driving through the village, and seeing the closed down bar, the abandoned corrals, the ruins of the original settlement, and the non-existent general store, there is a stark reminder that the history is here, but those who can recount it for you may not be.

Larry Martinez walks with his grandson in Arroyo del Agua, New Mexico

Coyote

Four miles west of Youngsville, located in a scenic valley cut by small streams and lined with red rock formations, is Coyote. This small settlement of a little over 300 residents is rich with history. Notorious within some circles, renowned in others, Coyote has been an influential part in the history of Rio Arriba.

According to The Roadside History of New Mexico, the town is named for Coyote Canyon, presumably named for the large population of the animals in the area. The initial settlers in Coyote came from Youngsville, and old Gallina, which was located in the northern Chama area. These were farmers and herders, with herds of goats and sheep, and a few cows. The territory was opened up, and homesteaders built a walled, fortified village in 1808. Located just north of the present day highway through town, where the church is today, the small cluster of connected houses offered protection. With walls, corrals, fields and ditches, the tiny settlement provided enough safety and shelter for the homesteaders to survive. The land was a part of the San Juaquin Land grant, given by the King of Spain, but largely unsettled at the time because of the natives. Initially, due to Utes raiding the village, Coyote was abandoned, and the villagers moved back to the safety of Abiquiú or to Santa Cruz. In 1846, after Kit Carson’s Long Walk, Coyote was reinhabited by the homesteaders, and now feeling safe in the area, began to build farmhouses. Early inhabitants, including the Valdez, Martinez, and Lovato families, once again began to herd their animals on the communal land. Only the rich had horses and cows. The homesteaders had their summer houses, small cabins, high in the mountains- up into the Resumidero area and the surrounding high lands. Here the cool temperatures during the summer were ideal for raising sheep and goats, and small gardens. In the winter, the residents would move down into the valley, into their winter homes along the acequias in Coyote, La Mesa and Arroyo del Agua. Due to the nature of the land grant system, expansion was the key: you could have as much land as you could fence. The village, along with its vegetable gardens and ditches, was private land. This land was willed and passed on, but there was also the communal land. The communal land was the portion of the land grant that belonged to everyone, and could be used by all. Hunting, grazing, and logging could all be done on the communal land by anyone, and because of the small population, there was no fighting over the land at the time.

Around 1917, the communal land was taken over by the National Forest Service. The villagers could no longer use the land for whatever they wished. It was required of them to purchase permits for grazing or logging, and the people were upset. Their way of life had been disrupted, and some of the residents would not stand for it. The discontent grew, and from it came the battles of Tijerina in the 1960’s and 70’s, desperately trying to regain the San Juaquin communal land for the unrestricted use by the community, and resenting any outsiders who tried to impose their ideals on the locals.

Coyote, and the surrounding settlements lived in a fairly sheltered style up until the mid 20th century. Traveling to Española was a huge event, taking two days by wagon on the unpaved roads. Perhaps only undertaken twice a year, the trip was the biggest event in many residents’ lives. Sheepskins, wool, pinon nuts, potatoes, and other products raised or gathered by the residents were loaded into the wagon to take to town to trade for other needed items. After a day’s travel, the villagers would often stay overnight in Abiquiú, and then move on to Española the next day. Upon arrival, they would go to the People’s Store, located where the Convento stands today, and commence trading. The People’s store was a huge trading post. It was right on the railroad tracks, and thus had easy access to trains to transport goods to and from town.

Arroyo del Agua, one satellite community of Coyote, was also a somewhat self-sustaining community at this time. In the 1930’s and 40’s, Arroyo del Agua had a store, a one-room schoolhouse, one gas station on the corner, and one across the street. Like most small villages, this arrangement worked out well for the residents. The children would walk to the one room schoolhouse, there was no long bus ride, and none of the residents had cars. The gas stations were for the people driving by on the road.

The houses were situated so the kitchen was close to the ditch, to easily access water. A garden was strategically placed between the acequia and the kitchen, so vegetables could be utilized easily. It was a relatively simple life, filled with hard work. When the mail would come into town, the teenagers would get on their horses and gather all their friends. They would sit up on the hill and watch the car bringing the mail make its progress into the village.

With World War II, many men from the area served their duty. Returning home to the small village, after having seen the lifestyles in the big cities, they began to feel how isolated their area was, how cut off from modern amenities it was. Cars began to be the popular thing- everyone had to have one, just like other Americans. Into the 50’s, the roads were paved, speeding contact with the world. It was easier to travel into the larger towns, and as a result, shopping habits changed. With the roads, school busses could travel easily, and the children were consolidated into group schools. While parts of the progress were beneficial, some aspects of it were not. The small gas stations and stores closed, as did the one-room schoolhouses.

Because of the lack of jobs, most of the men would go out of state for work. Many would take the chili train or, later, the bus from Cuba, and go up to Utah to herd sheep. The big ranches in Utah and Nevada would hire the men from Coyote and surrounding areas because they knew so much about herding sheep. Sheep herding, after all, had been the main way of life for decades, up until the time the Forest Service required the herds changed over to cattle. Up in Utah or Nevada, the men would work the summers, leaving the women behind, and return later in the year with cash. They would also go up to Alamosa and other parts of Colorado, for seasonal work. Gathering sugar beets, potatoes, beans, and any other work that needed to be done, they did it, and they did this up until recent years. Now less of this work is offered to the residents, with most of the labor being given to workers from other countries.

Tijerina was just one of the notorious residents of Coyote, living in his fenced house on the edge of town. In the satellite community of Arroyo del Agua, the Martinez family also had their share of notoriety. Los Mochos, or “the Mutilated,” frequently took the law into their own hands, in the style of Tijerina. It has been said that police officers will not patrol the area, and Coyote once elected its own sheriff and claimed the region as a sovereign nation, under its own laws and regulations. Coyote has been called the final frontier of the Wild West.

In the cyclical change experienced in Coyote and the surrounding areas, after a brief time of prosperity, followed by the lack of jobs and hard times, many are reverting back to simpler ways of living. There are two stores in town, where you can purchase gasoline or food. The elementary school, with its declining population, has become like a one-room schoolhouse again- this one in a larger building, but with one or two teachers instructing all the grades. Many people are moving away, towards the hopes of opportunity in the larger cities. The community is dying out. Affluent white people are moving in, who want little to do with the old ways of life or the rich culture. What is the future of communities like Coyote? Are they to become gentrified like Abiquiú, forgetting the history of the land they now call home? Only time will tell…

Gallina

Approximately 15 minutes west of Coyote, along winding NM 96, lies Gallina. The drive takes you alongside orchards and lush green fields, through areas with huge, old pine trees, and around giant red and yellow sandstone outcrops. Shrub oaks grow beside abandoned adobe houses, and newer pre-fab homes have been set up along the highway.

Gallina was settled in the early eighteen hundreds by grantees of the San Juaquin Land Grant. It consists of the spread out main settlement, and the offshoot of Gallina Creek two miles to the west. Similar to Youngsville and Coyote, Gallina was developed by farmers and ranchers when it was first settled, and being in Ute territory, raids forced early settlers back to the settlement made by Onate in Santa Cruz de la Canada. Eventually, Gallina was resettled and appears in trading documents in the 1820’s as a stop on the Armijo trade route and as a shorter route to California.

The Gallinas towers, called New Mexico’s lost cities by some, are possibly the first structures in the area. Archaeologists excavated the ruins in the early 1930’s, and found many forms of living units, in addition to multiple towers, which are rare in the southwest. These buildings were the site of devastation to those who built them, with skeletal remains showing violent deaths, but no evidence on who had attacked or why. Only the structures remain, to leave us with questions even today.

Early residents of Gallina would have had similar lifestyles to those in Coyote and the surrounding areas. They were herders from Abiquiú, who had built summer homes in Gallina to tend to their sheep. A church was established, in the mid 1800’s, along with an irrigation system. In the 1860’s, a treaty was reached with the Utes, which opened up trading with the tribe, which was relocated to a reservation in southern Colorado, and boosted the economy of the village, as well as the level of safety. Farming expanded, with crops of corn, wheat, and animal feed, and there was a general store opened in the area. Eventually, in 1888, a post office was established, but under the name Jacquez. Two years later, the name was changed to Gallina. The term means “chicken” in Spanish, but most likely refers to the wild turkeys common in the area.

Life in Gallina was very much the same up through the early 20th century. Gallina still supported itself largely on the farming economy, and the gardens, mills, and sheep provided most of what the residents needed. There were general stores in town where the villagers could purchase the few items that they could not provide for themselves. Many of the men would travel north to Utah or Nevada to work as herders or in the mines, returning with cash to spend. Due to the largely cash-less economy, the effects of the Great Depression were scarcely felt in Gallina.

During World War II, Gallina saw many of its young men, like so many of the communities in the area, go off to war, and come back with changed world views. Soon after the war, sawmills grew up in the little town, and many people moved to Gallina and were employed by the sawmills and as loggers. The sawmill boom lasted for a couple decades, but then, due to changing laws and regulations, all of the mills shut down eventually, taking with them the large number of wage paying jobs.

Many people moved away due to lack of work, and the population fell back to its current numbers. While many of the people who live in Gallina work for the Forest service, the State Highway department, or the Jemez Mountain School District and its administrative offices, many are forced to commute long distances. The farming is virtually nonexistent, and ranching is upheld by the hardy few, struggling to keep that part of Gallina’s history alive.

At close to 500 residents, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, Gallina is a formidable size, in comparison to the surrounding settlements. Today, Gallina is home to a single gas station, a few scattered churches, and the only high school to attend for students in the surrounding area. Tradition and culture are still alive in Gallina, and strong family ties bind the residents of the area closely. People still celebrate some of the old customs, like the matanza, or slaughter, and the feast day, according to SUN reports. Those who can survive on jobs in the area hold onto them, but many of the young people are moving away. Maybe they will return later in life, to retire to the demanding but simple life that has been the Gallina way for more than a century.

Lindrith

After passing through Gallina, west on NM 96, some gorgeous landscapes can be observed. Sandstone formations line the road, as do tree covered hills, reaching out from the surrounding mountains. Reds and yellows abound, and horses run in fenced fields cut by arroyos. It is here, rounding a sharp turn in the road, and turning onto NM 595, that is the land that makes up Lindrith.

This area was dotted with small settlements, Lindrith being just one of many, including those in Ojito Canyon, Largo, Tapacitoes, and Gavilan. Settled at around the same time, during the homesteading years, each of these small communities had something to offer at the time. Some had trading posts, or schools, and Lindrith and Ojito had post offices. Most of these had closed down by the mid 1960’s, but Lindrith remained.

Lindrith was opened for homesteaders in the early 1900’s. At that time, there was a post office and a trading post, opened by Mr. and Mrs. C. C. Hill in 1919, but no schools or churches. The settlement was named for the Hill’s son and stepson, Lindrith Cordell. Many of the initial residents were previous sharecrop farmers from Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The harsh life endured by most sharecroppers toughened the people to endure the meager lifestyle in Lindrith. Homesteaders were given 640 acres, and a portion of the land was used for farming, the new settlers growing wheat, corn, and beans on their land to survive. It was a tough life; often residents would trap coyotes or bobcats in the winter, and then go back to farming in the summer months. Most of the initial wave of people populating Lindrith and the surrounding townships didn’t have the skills or determination to stick it out, so they left. Not realizing the techniques required to farm in the area, or weather out the unpredictable climate, many sharecroppers sold their farms and moved away. The few that stayed were tough people, and they hung around to see Lindrith experience the best of its times. Most of these people were used to living in poverty. During the Great Depression, the effects were pretty much non-existent, since the lifestyle was used to doing without. Lindrith began to feel growing pains when oil was discovered, the first wells being drilled in the late 40’s and early 50’s, and the oil and gas fields opened up a whole new industry. Soon, there were enough families in the area to open up a high school, a Presbyterian church, a Baptist church, and a bar. Electricity came to Lindrith in the early 50’s, as did running water. Telephones were introduced in the 60’s. With the oil fields came the renovations. Some of the roads were improved, but to this day, most of the roads are still unpaved, and the main, paved road into town dead ends some 10 miles outside of town. The big oil companies did most of the road improvement during the 70’s to access the oil fields easily, so only those roads that would benefit them were improved. For some time, business was booming in Lindrith, but it would not last. People began to get restless, and many moved away for opportunities in larger cities. The Presbyterian Church shut its doors, as did the bar and the high school, after lack of students forced it to eliminate the upper grades. Today, the only school in Lindrith is a charter school, after the elementary school was shut down. The charter is doing well, according to Tony Schmitz, whose wife works at the school. Well into its third year, the charter has 23 students, who can attend up until the 8th grade. From there, they will be bussed into the high school in Gallina.

Very little farming is done in Lindrith now. Most people are working in the gas and oil fields, although a new ordinance no longer allows drilling on private land. Most of the work on the oil fields involves checking the wells, or pumping them, but with the regulations and the dropping oil prices, people living here have to look elsewhere for work. The farmland is being grown up with wheat grass, and deer and elk are raised on it, and used for private hunts. Hunting became the big industry of Lindrith around 25 years ago, and still remains so now. Construction is also a relatively large business, however employment rates have dropped. Construction companies that once boasted 15 or 20 employees are now down to less than five.

Lots of the land has changed hands since the first settlers moved in. There are some new people moving in, and some of the older residents have retired, but there are different people now. Most of the original families are either dead or gone, says Schmitz. The future of Lindrith may be bleak. With a population of about 350, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, there are few people in the area, and they can’t afford to lose any more families. Not too many young families are moving in, and worries about keeping the school open arise. Without the school, the community dies.

Summery

It is wonderful to speak with people who feel a strong tie to the area in which they live. Towns like Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith all have residents who value the heritage and history of the land that they and their ancestors have called home for decades. But history is not the only thing that keeps a community alive, especially if that history is being forgotten. Many of these small communities are slowly dying, the infusion of pride and resilience only keeping them crawling along. We have seen the devastating effects of greed and the need of a cash-based economy to the fullest extent in these settlements that once thrived under farming and herding based economies. Once a self-sustaining village, with its own school and small, but prosperous, stores, requiring only the minimal purchases from outside sources, is now a crumbling shell. Where the gas station stood is now a rundown adobe building, rusting cars lie in wait around its walls. In some ways, the way of life has stayed the same: still only one or two general stores in town. The Coyote elementary school has reverted back to the one-room schoolhouse system, involuntarily. There are still the occasional vegetable garden, and orchard, and alfalfa field. But more and more people are moving away. More and more of the elders, the ones who remember the history and pass it on, are gone. The history may not be what keeps the community alive, but it gives those who live in the community the strength and knowledge and desire to keep the community alive. It is these strong-willed members who make a difference. The education of our community members provides us with strong, proud community leaders who can make a difference. Go out and talk with your neighbors. Learn all you can from your older relatives. Listen and pay attention to the history of the area, your history. That is what makes a difference. You are the one that makes a difference. You are that which keeps a community alive and thriving.

Four miles west of Youngsville, located in a scenic valley cut by small streams and lined with red rock formations, is Coyote. This small settlement of a little over 300 residents is rich with history. Notorious within some circles, renowned in others, Coyote has been an influential part in the history of Rio Arriba.

According to The Roadside History of New Mexico, the town is named for Coyote Canyon, presumably named for the large population of the animals in the area. The initial settlers in Coyote came from Youngsville, and old Gallina, which was located in the northern Chama area. These were farmers and herders, with herds of goats and sheep, and a few cows. The territory was opened up, and homesteaders built a walled, fortified village in 1808. Located just north of the present day highway through town, where the church is today, the small cluster of connected houses offered protection. With walls, corrals, fields and ditches, the tiny settlement provided enough safety and shelter for the homesteaders to survive. The land was a part of the San Juaquin Land grant, given by the King of Spain, but largely unsettled at the time because of the natives. Initially, due to Utes raiding the village, Coyote was abandoned, and the villagers moved back to the safety of Abiquiú or to Santa Cruz. In 1846, after Kit Carson’s Long Walk, Coyote was reinhabited by the homesteaders, and now feeling safe in the area, began to build farmhouses. Early inhabitants, including the Valdez, Martinez, and Lovato families, once again began to herd their animals on the communal land. Only the rich had horses and cows. The homesteaders had their summer houses, small cabins, high in the mountains- up into the Resumidero area and the surrounding high lands. Here the cool temperatures during the summer were ideal for raising sheep and goats, and small gardens. In the winter, the residents would move down into the valley, into their winter homes along the acequias in Coyote, La Mesa and Arroyo del Agua. Due to the nature of the land grant system, expansion was the key: you could have as much land as you could fence. The village, along with its vegetable gardens and ditches, was private land. This land was willed and passed on, but there was also the communal land. The communal land was the portion of the land grant that belonged to everyone, and could be used by all. Hunting, grazing, and logging could all be done on the communal land by anyone, and because of the small population, there was no fighting over the land at the time.

Around 1917, the communal land was taken over by the National Forest Service. The villagers could no longer use the land for whatever they wished. It was required of them to purchase permits for grazing or logging, and the people were upset. Their way of life had been disrupted, and some of the residents would not stand for it. The discontent grew, and from it came the battles of Tijerina in the 1960’s and 70’s, desperately trying to regain the San Juaquin communal land for the unrestricted use by the community, and resenting any outsiders who tried to impose their ideals on the locals.

Coyote, and the surrounding settlements lived in a fairly sheltered style up until the mid 20th century. Traveling to Española was a huge event, taking two days by wagon on the unpaved roads. Perhaps only undertaken twice a year, the trip was the biggest event in many residents’ lives. Sheepskins, wool, pinon nuts, potatoes, and other products raised or gathered by the residents were loaded into the wagon to take to town to trade for other needed items. After a day’s travel, the villagers would often stay overnight in Abiquiú, and then move on to Española the next day. Upon arrival, they would go to the People’s Store, located where the Convento stands today, and commence trading. The People’s store was a huge trading post. It was right on the railroad tracks, and thus had easy access to trains to transport goods to and from town.

Arroyo del Agua, one satellite community of Coyote, was also a somewhat self-sustaining community at this time. In the 1930’s and 40’s, Arroyo del Agua had a store, a one-room schoolhouse, one gas station on the corner, and one across the street. Like most small villages, this arrangement worked out well for the residents. The children would walk to the one room schoolhouse, there was no long bus ride, and none of the residents had cars. The gas stations were for the people driving by on the road.

The houses were situated so the kitchen was close to the ditch, to easily access water. A garden was strategically placed between the acequia and the kitchen, so vegetables could be utilized easily. It was a relatively simple life, filled with hard work. When the mail would come into town, the teenagers would get on their horses and gather all their friends. They would sit up on the hill and watch the car bringing the mail make its progress into the village.

With World War II, many men from the area served their duty. Returning home to the small village, after having seen the lifestyles in the big cities, they began to feel how isolated their area was, how cut off from modern amenities it was. Cars began to be the popular thing- everyone had to have one, just like other Americans. Into the 50’s, the roads were paved, speeding contact with the world. It was easier to travel into the larger towns, and as a result, shopping habits changed. With the roads, school busses could travel easily, and the children were consolidated into group schools. While parts of the progress were beneficial, some aspects of it were not. The small gas stations and stores closed, as did the one-room schoolhouses.

Because of the lack of jobs, most of the men would go out of state for work. Many would take the chili train or, later, the bus from Cuba, and go up to Utah to herd sheep. The big ranches in Utah and Nevada would hire the men from Coyote and surrounding areas because they knew so much about herding sheep. Sheep herding, after all, had been the main way of life for decades, up until the time the Forest Service required the herds changed over to cattle. Up in Utah or Nevada, the men would work the summers, leaving the women behind, and return later in the year with cash. They would also go up to Alamosa and other parts of Colorado, for seasonal work. Gathering sugar beets, potatoes, beans, and any other work that needed to be done, they did it, and they did this up until recent years. Now less of this work is offered to the residents, with most of the labor being given to workers from other countries.

Tijerina was just one of the notorious residents of Coyote, living in his fenced house on the edge of town. In the satellite community of Arroyo del Agua, the Martinez family also had their share of notoriety. Los Mochos, or “the Mutilated,” frequently took the law into their own hands, in the style of Tijerina. It has been said that police officers will not patrol the area, and Coyote once elected its own sheriff and claimed the region as a sovereign nation, under its own laws and regulations. Coyote has been called the final frontier of the Wild West.

In the cyclical change experienced in Coyote and the surrounding areas, after a brief time of prosperity, followed by the lack of jobs and hard times, many are reverting back to simpler ways of living. There are two stores in town, where you can purchase gasoline or food. The elementary school, with its declining population, has become like a one-room schoolhouse again- this one in a larger building, but with one or two teachers instructing all the grades. Many people are moving away, towards the hopes of opportunity in the larger cities. The community is dying out. Affluent white people are moving in, who want little to do with the old ways of life or the rich culture. What is the future of communities like Coyote? Are they to become gentrified like Abiquiú, forgetting the history of the land they now call home? Only time will tell…

Gallina

Approximately 15 minutes west of Coyote, along winding NM 96, lies Gallina. The drive takes you alongside orchards and lush green fields, through areas with huge, old pine trees, and around giant red and yellow sandstone outcrops. Shrub oaks grow beside abandoned adobe houses, and newer pre-fab homes have been set up along the highway.

Gallina was settled in the early eighteen hundreds by grantees of the San Juaquin Land Grant. It consists of the spread out main settlement, and the offshoot of Gallina Creek two miles to the west. Similar to Youngsville and Coyote, Gallina was developed by farmers and ranchers when it was first settled, and being in Ute territory, raids forced early settlers back to the settlement made by Onate in Santa Cruz de la Canada. Eventually, Gallina was resettled and appears in trading documents in the 1820’s as a stop on the Armijo trade route and as a shorter route to California.

The Gallinas towers, called New Mexico’s lost cities by some, are possibly the first structures in the area. Archaeologists excavated the ruins in the early 1930’s, and found many forms of living units, in addition to multiple towers, which are rare in the southwest. These buildings were the site of devastation to those who built them, with skeletal remains showing violent deaths, but no evidence on who had attacked or why. Only the structures remain, to leave us with questions even today.

Early residents of Gallina would have had similar lifestyles to those in Coyote and the surrounding areas. They were herders from Abiquiú, who had built summer homes in Gallina to tend to their sheep. A church was established, in the mid 1800’s, along with an irrigation system. In the 1860’s, a treaty was reached with the Utes, which opened up trading with the tribe, which was relocated to a reservation in southern Colorado, and boosted the economy of the village, as well as the level of safety. Farming expanded, with crops of corn, wheat, and animal feed, and there was a general store opened in the area. Eventually, in 1888, a post office was established, but under the name Jacquez. Two years later, the name was changed to Gallina. The term means “chicken” in Spanish, but most likely refers to the wild turkeys common in the area.

Life in Gallina was very much the same up through the early 20th century. Gallina still supported itself largely on the farming economy, and the gardens, mills, and sheep provided most of what the residents needed. There were general stores in town where the villagers could purchase the few items that they could not provide for themselves. Many of the men would travel north to Utah or Nevada to work as herders or in the mines, returning with cash to spend. Due to the largely cash-less economy, the effects of the Great Depression were scarcely felt in Gallina.

During World War II, Gallina saw many of its young men, like so many of the communities in the area, go off to war, and come back with changed world views. Soon after the war, sawmills grew up in the little town, and many people moved to Gallina and were employed by the sawmills and as loggers. The sawmill boom lasted for a couple decades, but then, due to changing laws and regulations, all of the mills shut down eventually, taking with them the large number of wage paying jobs.

Many people moved away due to lack of work, and the population fell back to its current numbers. While many of the people who live in Gallina work for the Forest service, the State Highway department, or the Jemez Mountain School District and its administrative offices, many are forced to commute long distances. The farming is virtually nonexistent, and ranching is upheld by the hardy few, struggling to keep that part of Gallina’s history alive.

At close to 500 residents, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, Gallina is a formidable size, in comparison to the surrounding settlements. Today, Gallina is home to a single gas station, a few scattered churches, and the only high school to attend for students in the surrounding area. Tradition and culture are still alive in Gallina, and strong family ties bind the residents of the area closely. People still celebrate some of the old customs, like the matanza, or slaughter, and the feast day, according to SUN reports. Those who can survive on jobs in the area hold onto them, but many of the young people are moving away. Maybe they will return later in life, to retire to the demanding but simple life that has been the Gallina way for more than a century.

Lindrith

After passing through Gallina, west on NM 96, some gorgeous landscapes can be observed. Sandstone formations line the road, as do tree covered hills, reaching out from the surrounding mountains. Reds and yellows abound, and horses run in fenced fields cut by arroyos. It is here, rounding a sharp turn in the road, and turning onto NM 595, that is the land that makes up Lindrith.

This area was dotted with small settlements, Lindrith being just one of many, including those in Ojito Canyon, Largo, Tapacitoes, and Gavilan. Settled at around the same time, during the homesteading years, each of these small communities had something to offer at the time. Some had trading posts, or schools, and Lindrith and Ojito had post offices. Most of these had closed down by the mid 1960’s, but Lindrith remained.

Lindrith was opened for homesteaders in the early 1900’s. At that time, there was a post office and a trading post, opened by Mr. and Mrs. C. C. Hill in 1919, but no schools or churches. The settlement was named for the Hill’s son and stepson, Lindrith Cordell. Many of the initial residents were previous sharecrop farmers from Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The harsh life endured by most sharecroppers toughened the people to endure the meager lifestyle in Lindrith. Homesteaders were given 640 acres, and a portion of the land was used for farming, the new settlers growing wheat, corn, and beans on their land to survive. It was a tough life; often residents would trap coyotes or bobcats in the winter, and then go back to farming in the summer months. Most of the initial wave of people populating Lindrith and the surrounding townships didn’t have the skills or determination to stick it out, so they left. Not realizing the techniques required to farm in the area, or weather out the unpredictable climate, many sharecroppers sold their farms and moved away. The few that stayed were tough people, and they hung around to see Lindrith experience the best of its times. Most of these people were used to living in poverty. During the Great Depression, the effects were pretty much non-existent, since the lifestyle was used to doing without. Lindrith began to feel growing pains when oil was discovered, the first wells being drilled in the late 40’s and early 50’s, and the oil and gas fields opened up a whole new industry. Soon, there were enough families in the area to open up a high school, a Presbyterian church, a Baptist church, and a bar. Electricity came to Lindrith in the early 50’s, as did running water. Telephones were introduced in the 60’s. With the oil fields came the renovations. Some of the roads were improved, but to this day, most of the roads are still unpaved, and the main, paved road into town dead ends some 10 miles outside of town. The big oil companies did most of the road improvement during the 70’s to access the oil fields easily, so only those roads that would benefit them were improved. For some time, business was booming in Lindrith, but it would not last. People began to get restless, and many moved away for opportunities in larger cities. The Presbyterian Church shut its doors, as did the bar and the high school, after lack of students forced it to eliminate the upper grades. Today, the only school in Lindrith is a charter school, after the elementary school was shut down. The charter is doing well, according to Tony Schmitz, whose wife works at the school. Well into its third year, the charter has 23 students, who can attend up until the 8th grade. From there, they will be bussed into the high school in Gallina.

Very little farming is done in Lindrith now. Most people are working in the gas and oil fields, although a new ordinance no longer allows drilling on private land. Most of the work on the oil fields involves checking the wells, or pumping them, but with the regulations and the dropping oil prices, people living here have to look elsewhere for work. The farmland is being grown up with wheat grass, and deer and elk are raised on it, and used for private hunts. Hunting became the big industry of Lindrith around 25 years ago, and still remains so now. Construction is also a relatively large business, however employment rates have dropped. Construction companies that once boasted 15 or 20 employees are now down to less than five.

Lots of the land has changed hands since the first settlers moved in. There are some new people moving in, and some of the older residents have retired, but there are different people now. Most of the original families are either dead or gone, says Schmitz. The future of Lindrith may be bleak. With a population of about 350, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, there are few people in the area, and they can’t afford to lose any more families. Not too many young families are moving in, and worries about keeping the school open arise. Without the school, the community dies.

Summery

It is wonderful to speak with people who feel a strong tie to the area in which they live. Towns like Youngsville, Coyote, Gallina and Lindrith all have residents who value the heritage and history of the land that they and their ancestors have called home for decades. But history is not the only thing that keeps a community alive, especially if that history is being forgotten. Many of these small communities are slowly dying, the infusion of pride and resilience only keeping them crawling along. We have seen the devastating effects of greed and the need of a cash-based economy to the fullest extent in these settlements that once thrived under farming and herding based economies. Once a self-sustaining village, with its own school and small, but prosperous, stores, requiring only the minimal purchases from outside sources, is now a crumbling shell. Where the gas station stood is now a rundown adobe building, rusting cars lie in wait around its walls. In some ways, the way of life has stayed the same: still only one or two general stores in town. The Coyote elementary school has reverted back to the one-room schoolhouse system, involuntarily. There are still the occasional vegetable garden, and orchard, and alfalfa field. But more and more people are moving away. More and more of the elders, the ones who remember the history and pass it on, are gone. The history may not be what keeps the community alive, but it gives those who live in the community the strength and knowledge and desire to keep the community alive. It is these strong-willed members who make a difference. The education of our community members provides us with strong, proud community leaders who can make a difference. Go out and talk with your neighbors. Learn all you can from your older relatives. Listen and pay attention to the history of the area, your history. That is what makes a difference. You are the one that makes a difference. You are that which keeps a community alive and thriving.

Cows being fed in snow covered Coyote, New Mexico, field in the middle of winter.

NM 96 winding into Youngsville, New Mexico

An apparently abandoned church sits at the end of a dirt road with a dramatic plateau backdrop in Gallina, New Mexico

Sweeping excess gravel off a newly resurfaced NM 96 in Gallina, New Mexico

Partially plowed field being prepared for spring planting in Coyote, New Mexico.

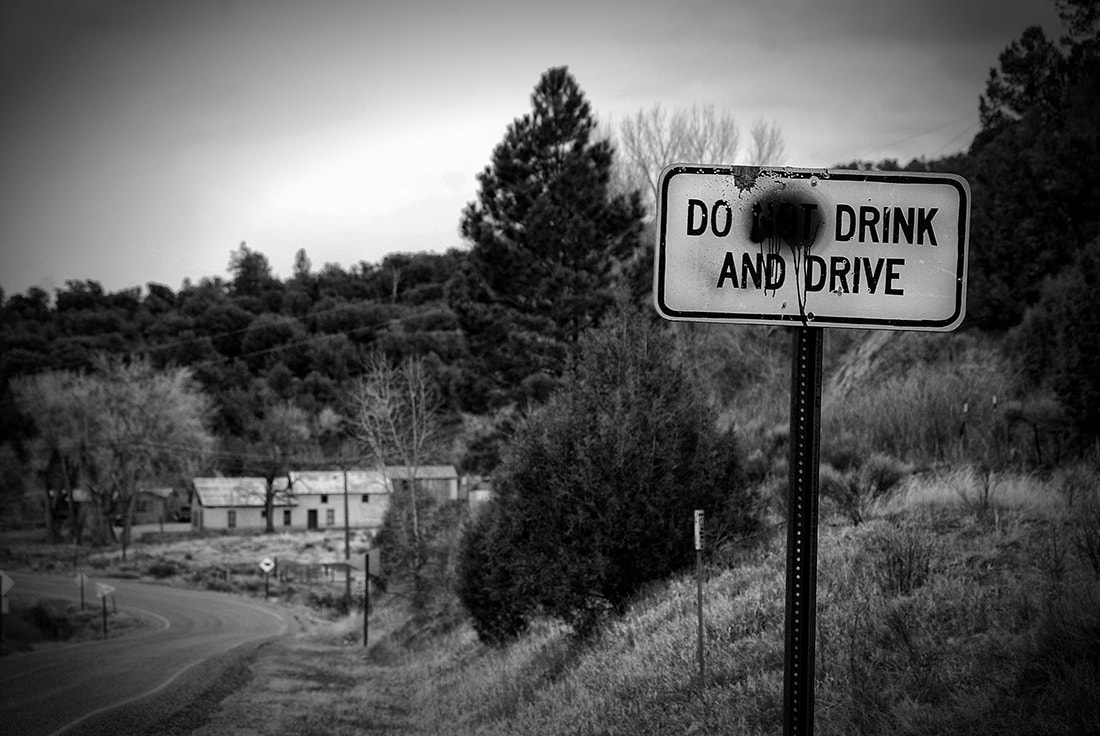

Someone apparently thought it humorous to "edit" this road sign in an attempt to call attention to the number of drivers

who drink and drive in Rio Arriba County and New Mexico. This was photographed on NM 96 on the eastern edge of Gallina, New Mexico

who drink and drive in Rio Arriba County and New Mexico. This was photographed on NM 96 on the eastern edge of Gallina, New Mexico

Two motorcyclists cruise on NM 96 a little west of Youngsville, New Mexico.

NM 96 is a popular route to take when heading to Chaco Canyon and the Bisti Badlands.

NM 96 is a popular route to take when heading to Chaco Canyon and the Bisti Badlands.

It's rare to see a dead coyote on a New Mexico road. The animals are usually very wary of roadways and don't get hit by cars often. This was a younger coyote and perhaps hadn't learned to be as cautious as it should have been. Taken on NM 96 a couple miles east of Youngsville, New Mexico.

Flowers line a snow fence in Gallina, New Mexico

Moon setting over L&A Jacquez Ranch gate, Gallina, New Mexico

Youngsville, New Mexico, church

School bus on HNM 96 in Youngsville on early morning run to pick up students. Cerro Pedernal serves as a backdrop.

Coyote Crossing general store is currently closed and looking for a new owner.

Panorama of Youngsville church with amazing sunset.

Naomi Martinez brushes one of her family's horses.

Cerro Pedernal with the sun peeking through heavy cloud cover seen from NM 96 east of Youngsville, New Mexico.

NM 96 winds through Arroyo del Agua just west of Coyote, New Mexico,

as is seems to head directly toward Cerro Pedernal.

as is seems to head directly toward Cerro Pedernal.

To contact Bob Eckert for assignments, consultations or workshops, please email [email protected]

or use the contact form on the About page

or use the contact form on the About page