Cumbres & Toltec Railroad, Chama, New Mexico

|

Mike Thode (above right) talks with Manuel Torrez while the two hostlers prepare to move two steam engines in the Cumbres & Toltec railyard.

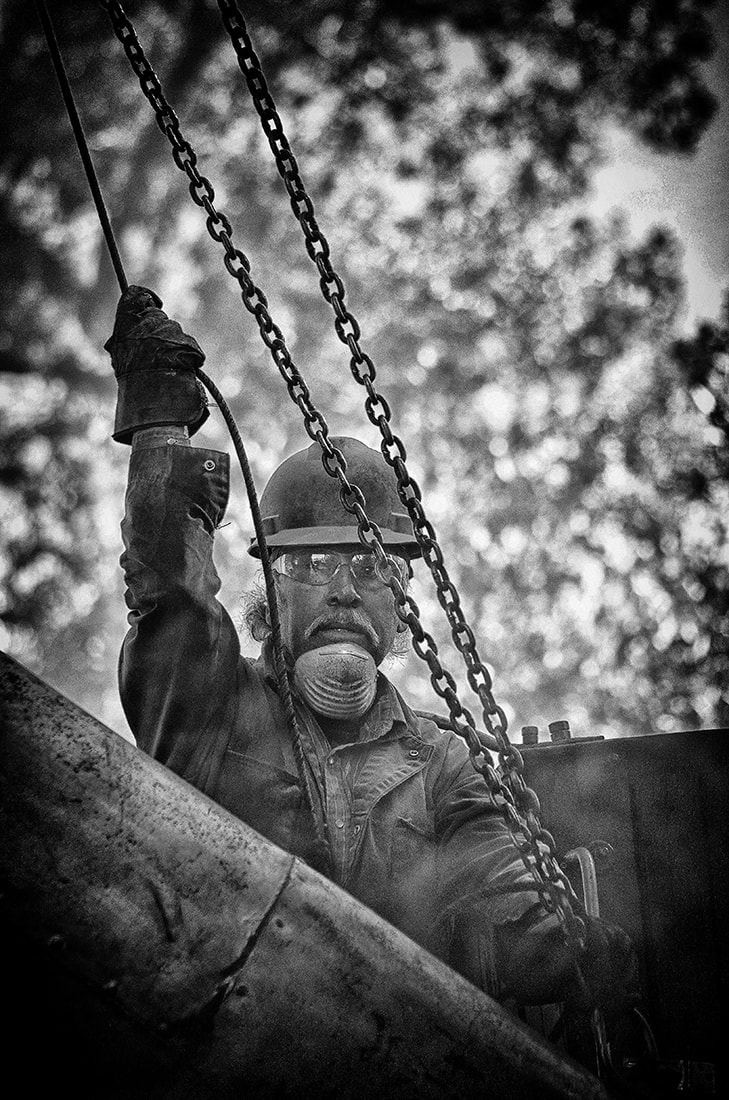

A railyard worker (above) adds sand to a tank on one of the stream engines prior to the train departing the Chama station. The sand is put on the rails and provides added traction for the engine in certain circumstances.

Manual Torres (below) uses steam to clean one of the steam engines before it departs the Chama station to Antonito, Colorado. |

Story and photos by Bob Eckert

On a recent morning in Chama, New Mexico, Mike Thode and Manuel Torrez were getting two steam engines ready for service. They were filling up both with water and coal, and cleaning the engines thoroughly since coal powered steam engines create a lot of dust and smoke, which tends to cover the trains making cleaning something that is done frequently. When one visitor asked Thode if he was an engineer, Thode replied, "I'm a hostler." Hostling is the action of shuttling a locomotive from the yard to the engine house or vice versa. But Thode seems to be something of a Renaissance railroad man, doing much more than just shutting trains in the railyard. He is a mechanic and actually fabricates parts for the trains, since there are manufactures now who you can order parts from. First a bit of Cumbres and Toltec history before a brief tour of the railyards. The Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad was originally constructed in 1880 as part of the Rio Grande’s San Juan Extension, which served the silver mining district of the San Juan mountains in southwestern Colorado. Like all of the Rio Grande at the time, it was built to a gauge of 3 feet between the rails, instead of the more common 4 feet, 8-1/2 inches that became standard in the United States. The inability to interchange cars with other railroads led the Rio Grande to begin converting its tracks to standard gauge in 1890. However, with the repeal of the Sherman Act in 1893 and its devastating effect on the silver mining industry, traffic over the San Juan Extension failed to warrant conversion to standard gauge. Over the ensuing decades it became an isolated anachronism, receiving its last major upgrades in equipment and infrastructure in the 1920s. A post-World War II natural gas boom brought a brief period of prosperity to the line, but operations dwindled to a trickle in the 1960s. Finally, in 1969 the Interstate Commerce Commission granted the Rio Grande’s request to abandon its remaining narrow gauge main line trackage, thereby ending the last use of steam locomotives in general freight service in the United States. Most of the abandoned track was dismantled soon after the ICC’s decision, but through the combined efforts of an energetic and resourceful group of railway preservationists and local civic interests, the most scenic portion of the line was saved. In 1970, Colorado and New Mexico jointly purchased the track and line-side structures from Antonito to Chama, nine steam locomotives, over 130 freight and work cars, and the Chama yard and maintenance facility, for $547,120. The C&TS began hauling tourists the next year. A brief tour. Thode invited a visitor to come up into one of the engines and inspect the interior. The firebox. In steam locomotives, the firebox is a chamber in which a fire is made to produce sufficient heat to create steam once the hot gases created there are carried into the adjacent boiler via tubes or flues according to Thode. "This door closes slower than it should, but I've got more important things to do at the moment," Those said, as he opened the firebox door to inspect the fire. Even though the engine was sitting still in the railyard, and the fire wasn't a roaring as it might have been during a trip, the interior of the cab is still very warm. Thode's co-worker, Manuel Torrez, is standing outside the engine motioning Thode to reverse to they can couple two engines together to save coal while they move them up the track to fill them with water and then coal. When that is done, the engines are moved to an open area where Thode and Torrez clean them off with high pressure hoses. The engines are then moved into place so Torrez can fill their water tanks. Then the engines are shuttled onto another track, which is where the duo will resupply each train with coal. It's fascinating walking around the railyard. The trains are massive and noisy, but it's like taking a free trip back into time. A word of caution, however. This is a working railyard, so you need to be aware of your surroundings. There are plenty of things to trip over and, when the trains are being shuttled, there's the possibility of being run over by a locomotive, albeit a slim one as the train workers are observant and aware of sightseers. And since these are coal fired trains, there is a lot of coal dust in the air around the engines and, when they are running, a lot of smoke being produced. |

To contact Bob Eckert for assignments, consultations or workshops, please email [email protected]

or use the contact form on the About page

or use the contact form on the About page