Lowriders

|

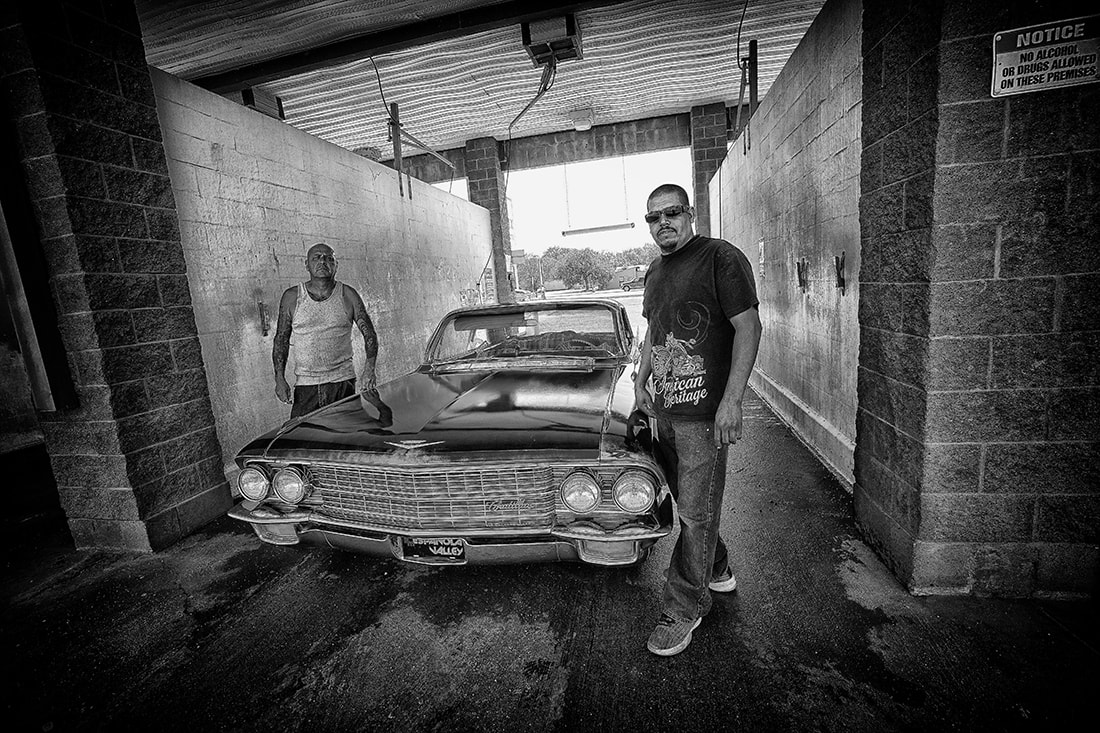

Eppie Martinez (seated) and his right hand man, Ernie Lopez, with two cars waiting their attention at Red's Old School in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

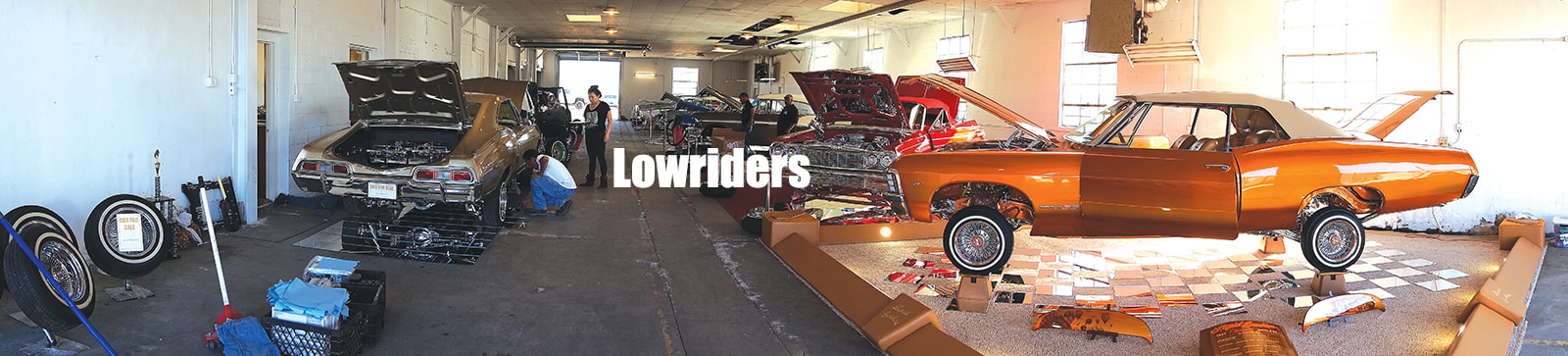

Two cars await custom work at Red's Old School in Old Town Albuquerque , New Mexico. Red's is owned by Chimayó, New Mexico native Eppie Martinez

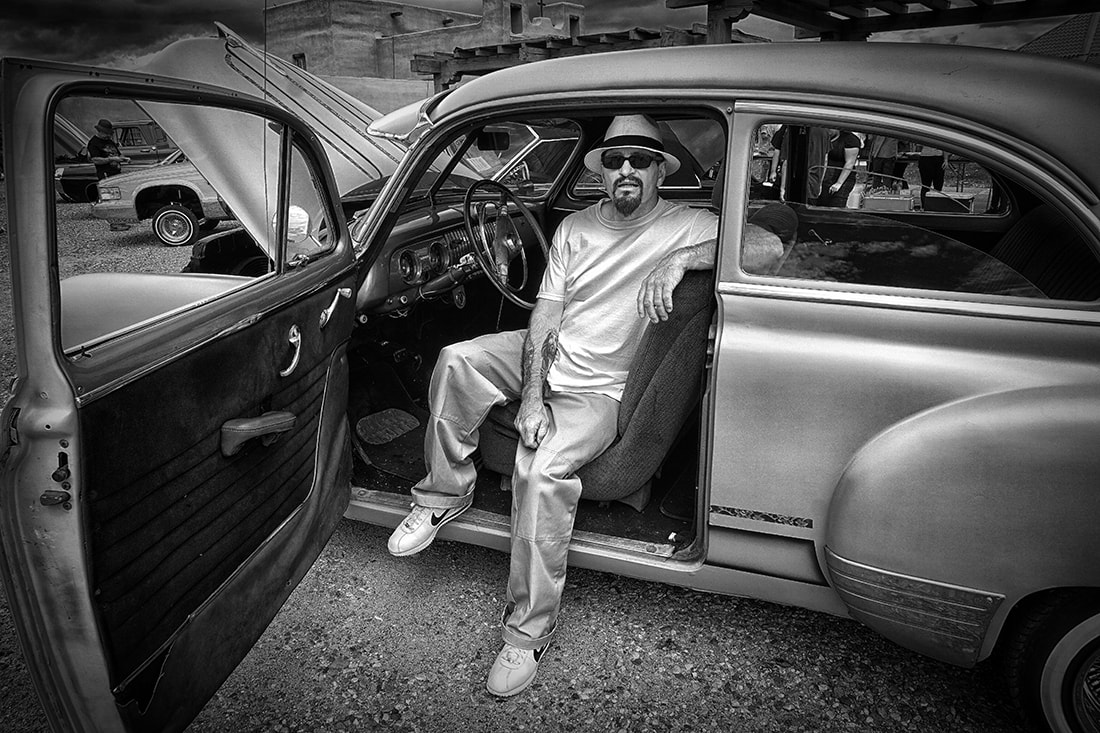

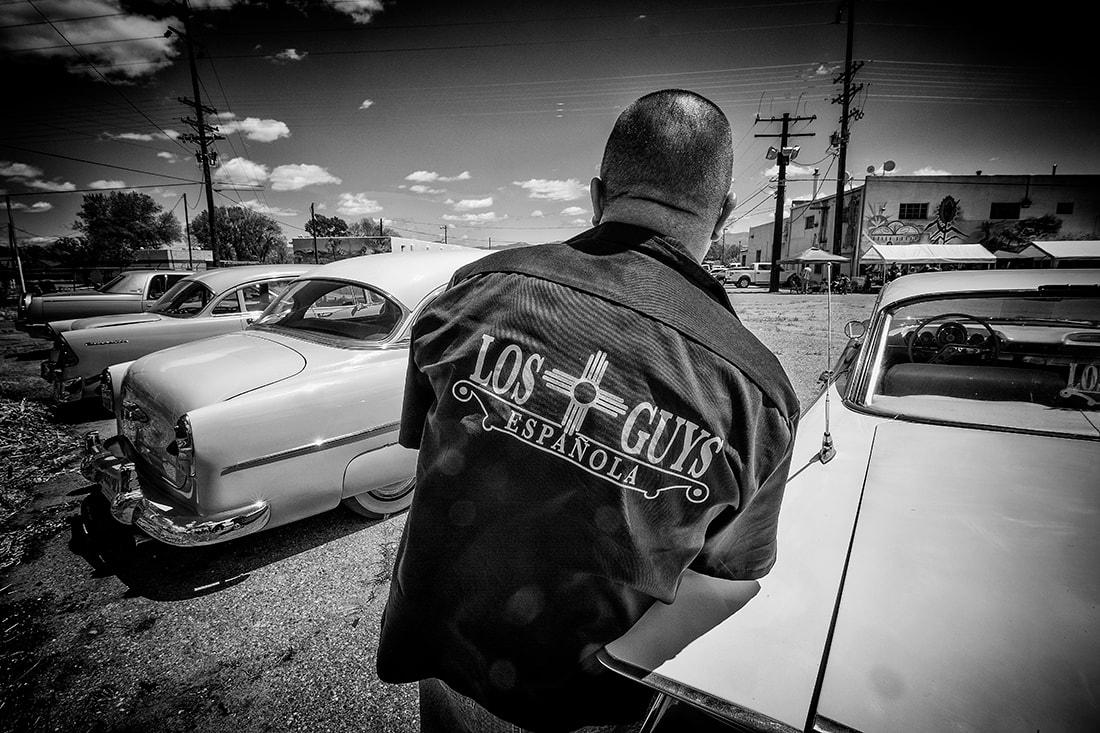

Eppie Martinez practices before a hopping contest at a car show in Española, New Mexico

Eppie Martinez stands in the doorway of Red's Old School in Old Town Albuquerque.

|

Story and photos by Bob Eckert

Lowrider hydraulics came about, not because they make a car hop or ride around corners on three wheels, which admittedly are terrific benefits of the technology, but for pragmatic reasons. Eppie Martinez owns Red’s Old School. He said hydraulics became part of lowriders because of the poor state of roads, and locations of rural garages, where the cars were created. Raising the car was necessary to get it over ruts and rocks and speed bumps in the road to get the car out. “Back in the day in Chimayó you’d go through arroyos, and every arroyo would go to somebody’s house,” Martinez said. “A lowrider is low — as low as you can go is the best — but if it’s that low, you ain’t getting out where you’re at. Back then we lived in arroyos and on dirt roads. It was the longest ride to get to that highway, but it was worth it. That’s just how we are, bringing that car out.” Lowrider owners in California loved the idea of raising and lowering their cars. It was entertaining for bystanders and fun for passengers, police however were not so enthralled with the trend. That’s where Vehicle Code 24008 came in stating it thereby illegal to operate any car modified so that any part was lower than the bottoms of its wheel rims. As with all rules, however, there are those who feel it’s their responsibility to bend or break them, hence the use of hydraulics. When a lowrider would see a police officer, or hear about one up ahead from other cruisers, he or she could raise the car, via the hydraulics, to make it “legal.” Martinez said there are two types of lifts most used today; hydraulics and air bags. It’s hydraulics “For me, I’d use hydraulics,” Martinez admitted. “Air Ride can only do so much. But some of them can do what hydraulics can, but only for a little bit. Hydraulics can go on and on until the batteries are dead.” Conversely, when the air is gone the bags are useless, Martinez said. However, he said air bags can do some crazy stuff. “Back about 10 years ago they weren’t allowed because it wasn’t hydraulic,” Martinez said. “So then these guys started making these trucks do things like, ‘Oh my God.’ And a lot of the guys want the ride but they don’t want the bounciness (hard ride of the traditional ‘cut’ car as opposed to air ride) so they go with Air Ride, these little pillows here.” An Air Ride suspension simply replaces coil springs with flexible, rubber, pressure-filled bags of air. These bags are inflated or deflated through a series of electrical controls as necessary, giving it a signature smooth ride. Hydraulic suspensions raise and lower much more quickly than air bag suspension because hydraulic fluid doesn’t take as long to compress. And for a longtime lowrider like Martinez, they are desired because they are traditional. Martinez is the go-to hydraulics guy. If you mention hydraulics, Red’s or Martinez’s name will come into play. But with Red’s, Martinez has gone from just hydraulics to a full service shop: upholstery, paint, full restoration. Martinez said each car is different and so there is no conventional solution — each job is custom. Martinez then pointed to a car near the lift, “He wants something simple, just a little shake and rattle.” Others might want something very radical. “I tell these guys that when they bring a car to me, I treat it like my own,” Martinez said. Martinez learned about cars primarily from his father, Ray, who was a mechanic and worked for Boeing in California before returning to Chimayó and eventually opening his own shop. “Going back a bit, there were no places like this (Reds Old School), there were backyard guys,” Martinez said. “Homies helping out a homie." Martinez said that just like the way he learned from his father, new generations have learned to love lowriders, but with the new generation there are constant changes. One of those changes is the hopping contests. Just physics “Our cars now can hop over 100 inches. Back then if you jumped over a beer can you were like the baddest guy there in town,” Martinez said, reminiscing about “Back in the Day,” and then shifting to the present. “It’s a whole new generation. It’s not about the amount of batteries, it’s not about the amount of metal, it’s not the size of tires or what particular vehicle anymore. Now it’s more about the weight. You look at some of these cars and they have beams instead of batteries because it’s easier to do that and quicker than trying to build something to do what they do.” When Martinez mentions weight and beams he’s referring to basic physics. “Your granddaughter on a teeter totter on one side and you on the other. What’s going to happen?” he asked. “Instead of doing it the hard way like we grew up doing, now they are trying to do it an easier way. For us, it’s not fair.” He mentioned a fellow with whom they recently competed against, who had an extended cab truck as opposed to Red’s standard size truck and in the back of the long bed was a large, heavy beam. With the longer wheelbase and weight in the back, physics took over and let the longer truck hop higher. “Eight or nine years ago, Lowrider Magazine had the big thing about having your car standing,” Martinez said. “Now, the hard part was making it come back down by itself. Before you only had one switch you were allowed and then there was the double switch, where you were sending it up and then hit another one to send it down. It’s more on the competitive side, not making it so easy.” Essentially sponsors are trying to enhance the entertainment value of the hopping contests by lessening rules and making it easier to reach higher hops, but this comes at the expense of tradition, at least to hear Martinez. “You can’t bring back the good old days like they say, all you can do is remember them,” Martinez said. “That was when hopping was hopping, you had rules. Now there are no rules.” |

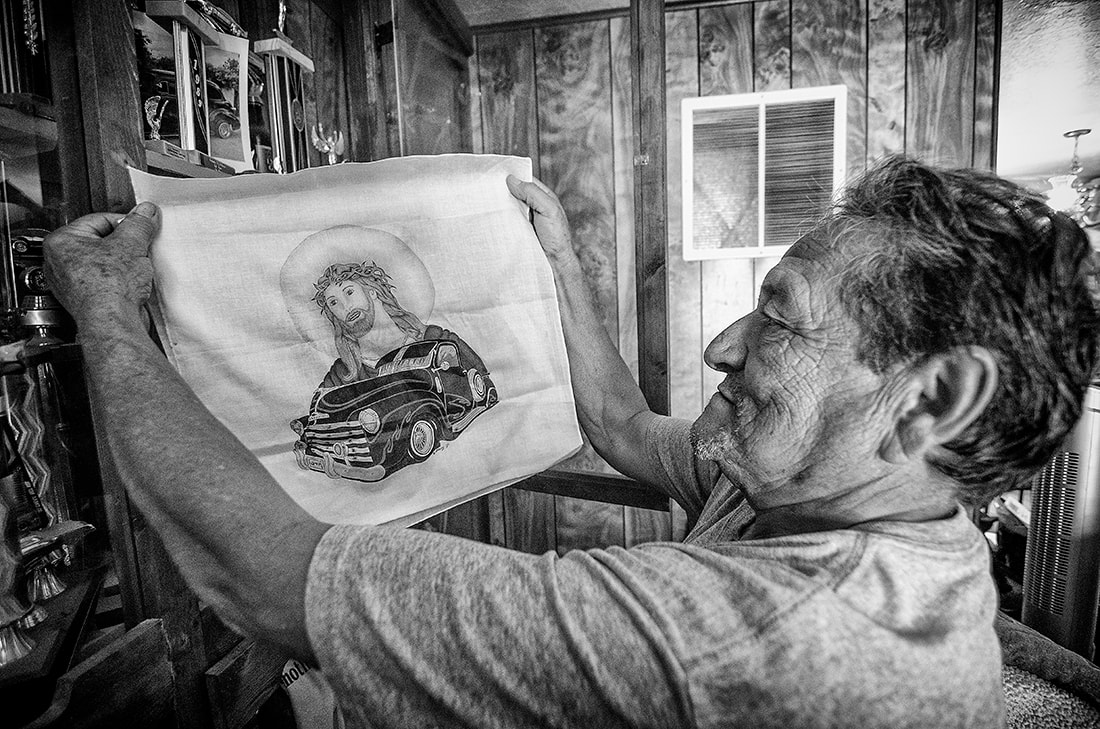

Eppie Martinez, of Chimayó, New Mexico, exhibits his car hopping prowess at the 2019 Lowrider Day held on the Española Plaza. Martinez's father, Ray Martinez, is known as one of the most knowledgeable hydraulics experts in Northern New Mexico.

Randy Ortiz Martinez Lowrider Mural

Story and photos by Bob Eckert

Although Chimayóan Randy Ortiz Martinez doesn’t want to be put in a pigeonhole in terms of what he paints, it’s easy for a viewer of his work to come to the conclusion he is a consummate portraitist.

You look at his smaller works — ‘smaller’ being a relative term because his ‘smaller’ pieces measure about four by five feet. But that aside, his ‘portraits’ are telling and complicated and really finely crafted. From the small, to his most current ‘portrait’, which can be seen on the side of one of the storage units along La Joya Street in Espanola, New Mexico. Needless to say, it’s considerably larger than four by five feet — standing about two stories tall.

In addition to Martinez’s canvas works, he has worked on a lot of murals, and you get the feeling after speaking with him, and hearing him talk about murals, that they really hold a special place in his heart.

The current mural on La Joya Street is different from his past murals in that it is the first one he has done using brushes instead of spray paint.

It is the first in what Martinez would like to be an ongoing series of mural portraits of people who are important to the Valley. He talks about this current one a bit.

“His name is Nolan Martinez and he had a lot to do with lowriding in Northern New Mexico. They did documentaries on him in the ‘60s and ‘70s. They did an exhibit on car culture in New Mexico at the Palace of the Governors a while back and they showed that documentary and he also helped build a car the Smithsonian bought and has on display in Washington. One of his poems is there, also. He represents a lot of Northern New Mexico culture.”

And Martinez’s use of brushes for the fine details shows marvelously in the Nolan Martinez mural. When viewed from across La Joya Street, the mural is well defined and executed, but what makes it stand apart from many murals one might come across is that when you move closer, the details that Martinez has taken the time to put into this painting make it one that can be inspected closely. It draws you in as a fine canvas painting would draw you in and you can spend quite some time looking at it and wondering about the person who is the subject.

After visiting with the artist, and looking at the mural firsthand, I found myself looking up Nolan Martinez on the Internet to find out more about him and his history in the Valley. You realize a painting has struck a cord when it prompts you to investigate its subject further in some manner after you have seen it.

As he speaks, Martinez points at some of his other murals that he is showing on a computer screen. His mural work is very facile and, even with some of the unfinished pieces, have a very sophisticated look. These are not ‘just’ murals. They are fine art on a very large scale.

“I love murals because it’s not just a painting that some person is going to put up on their wall and hardly anyone gets to see it.” Martinez says emphatically, reinforcing your impression that murals, and portraits, are going to play a very important part in the career of this young artist. “The thing with murals is that a lot of people don’t have money to go into galleries or even to buy a piece of artwork and that’s why it’s kind of a out of the social norm, especially in communities like this, and I think murals are good because they are for everybody. It’s not just for one person or for a gallery. It’s not a selfish act, which is what art, I think, ideally should be all about. It’s not supposed to be something selfish. It needs to be for everybody. I think that’s what’s cool about murals. It’s kind of like giving back.”

He says he has a particular interest in people that might be considered marginalized.

“I guess growing up in Chimayó, I really want to paint the people from here (the Espanola Valley) and I think that is part of the reason why I am in the position of painting people right now. People that are in rural areas or people that (society) forgets about. I think those are very interesting people.”

Martinez likes realism, perhaps it’s another reason he often paints people. But when asked about influences, he brings up a fairly eclectic mix:

“When I first started painting, Caravaggio was a real influence. Caravaggio, Vermeer, Michelangelo… it depends on what you’re doing. With painting they were like my main inspiration because Vermeer would do peasants and Caravaggio and the way he used his lighting. And everything he painted was so real (he didn’t gloss it over or romanticize his subjects) like with the beheading painting. She’s cutting off his head and there is blood squirting out and this was like in the 1500s. It was real as opposed to renaissance painters where everything was subtle.” He says, and then continues. “And most recently I’ve been looking at a lot of street art: Conner Harrington. The Mack. A little bit of everything. Also Richard Serra. Kandinsky. A lot of contemporary.”

“Since I started doing murals, my paintings on canvas have been really fast. It’s weird. Oh definitely. (That painting murals has been beneficial to his canvas work) I don’t know if it’s like one of those things, like feeling secure. On the scaffolding, I didn’t really need those bars that were around me. They were just there. But mentally you feel secure. I think it’s like that, once you tackle a big surface (like a large mural) like a wall, then when you look at a canvas it’s… I guess working big is more fun. It’s not so confined. At the same time, when you’re done, it gives the viewer a whole different perspective, too, because all of a sudden it becomes more of an experience rather than just looking at a (smaller, canvas) painting.”

Like, sure… and it’s over before he knows it.

Although Martinez grew up doing representational pieces, he’s become more acquainted with more contemporary art in his studies at Santa Fe University of Art and Design. And although it does seem like he favors representational art — and art that features the human form — you can see in some of his current work that he has been incorporating some of this newfound contemporary knowledge.

“Anything that looks real is interesting to me. It catches me.” Martinez enthuses. “I was never a big fan of abstract work until I went to school (he laughs), since it’s a conceptual art school. I always thought abstract art was something anybody could do, but even if it does look that way it’s all in how you express yourself. By the way you use a brushstroke or something. There’s something intriguing about that. I don’t feel I need to choose one or the other (representational vs. abstract). I primarily started painting and drawing realistically and I figure that’s a skill I can incorporate, also, with something abstract.”

Although Chimayóan Randy Ortiz Martinez doesn’t want to be put in a pigeonhole in terms of what he paints, it’s easy for a viewer of his work to come to the conclusion he is a consummate portraitist.

You look at his smaller works — ‘smaller’ being a relative term because his ‘smaller’ pieces measure about four by five feet. But that aside, his ‘portraits’ are telling and complicated and really finely crafted. From the small, to his most current ‘portrait’, which can be seen on the side of one of the storage units along La Joya Street in Espanola, New Mexico. Needless to say, it’s considerably larger than four by five feet — standing about two stories tall.

In addition to Martinez’s canvas works, he has worked on a lot of murals, and you get the feeling after speaking with him, and hearing him talk about murals, that they really hold a special place in his heart.

The current mural on La Joya Street is different from his past murals in that it is the first one he has done using brushes instead of spray paint.

It is the first in what Martinez would like to be an ongoing series of mural portraits of people who are important to the Valley. He talks about this current one a bit.

“His name is Nolan Martinez and he had a lot to do with lowriding in Northern New Mexico. They did documentaries on him in the ‘60s and ‘70s. They did an exhibit on car culture in New Mexico at the Palace of the Governors a while back and they showed that documentary and he also helped build a car the Smithsonian bought and has on display in Washington. One of his poems is there, also. He represents a lot of Northern New Mexico culture.”

And Martinez’s use of brushes for the fine details shows marvelously in the Nolan Martinez mural. When viewed from across La Joya Street, the mural is well defined and executed, but what makes it stand apart from many murals one might come across is that when you move closer, the details that Martinez has taken the time to put into this painting make it one that can be inspected closely. It draws you in as a fine canvas painting would draw you in and you can spend quite some time looking at it and wondering about the person who is the subject.

After visiting with the artist, and looking at the mural firsthand, I found myself looking up Nolan Martinez on the Internet to find out more about him and his history in the Valley. You realize a painting has struck a cord when it prompts you to investigate its subject further in some manner after you have seen it.

As he speaks, Martinez points at some of his other murals that he is showing on a computer screen. His mural work is very facile and, even with some of the unfinished pieces, have a very sophisticated look. These are not ‘just’ murals. They are fine art on a very large scale.

“I love murals because it’s not just a painting that some person is going to put up on their wall and hardly anyone gets to see it.” Martinez says emphatically, reinforcing your impression that murals, and portraits, are going to play a very important part in the career of this young artist. “The thing with murals is that a lot of people don’t have money to go into galleries or even to buy a piece of artwork and that’s why it’s kind of a out of the social norm, especially in communities like this, and I think murals are good because they are for everybody. It’s not just for one person or for a gallery. It’s not a selfish act, which is what art, I think, ideally should be all about. It’s not supposed to be something selfish. It needs to be for everybody. I think that’s what’s cool about murals. It’s kind of like giving back.”

He says he has a particular interest in people that might be considered marginalized.

“I guess growing up in Chimayó, I really want to paint the people from here (the Espanola Valley) and I think that is part of the reason why I am in the position of painting people right now. People that are in rural areas or people that (society) forgets about. I think those are very interesting people.”

Martinez likes realism, perhaps it’s another reason he often paints people. But when asked about influences, he brings up a fairly eclectic mix:

“When I first started painting, Caravaggio was a real influence. Caravaggio, Vermeer, Michelangelo… it depends on what you’re doing. With painting they were like my main inspiration because Vermeer would do peasants and Caravaggio and the way he used his lighting. And everything he painted was so real (he didn’t gloss it over or romanticize his subjects) like with the beheading painting. She’s cutting off his head and there is blood squirting out and this was like in the 1500s. It was real as opposed to renaissance painters where everything was subtle.” He says, and then continues. “And most recently I’ve been looking at a lot of street art: Conner Harrington. The Mack. A little bit of everything. Also Richard Serra. Kandinsky. A lot of contemporary.”

“Since I started doing murals, my paintings on canvas have been really fast. It’s weird. Oh definitely. (That painting murals has been beneficial to his canvas work) I don’t know if it’s like one of those things, like feeling secure. On the scaffolding, I didn’t really need those bars that were around me. They were just there. But mentally you feel secure. I think it’s like that, once you tackle a big surface (like a large mural) like a wall, then when you look at a canvas it’s… I guess working big is more fun. It’s not so confined. At the same time, when you’re done, it gives the viewer a whole different perspective, too, because all of a sudden it becomes more of an experience rather than just looking at a (smaller, canvas) painting.”

Like, sure… and it’s over before he knows it.

Although Martinez grew up doing representational pieces, he’s become more acquainted with more contemporary art in his studies at Santa Fe University of Art and Design. And although it does seem like he favors representational art — and art that features the human form — you can see in some of his current work that he has been incorporating some of this newfound contemporary knowledge.

“Anything that looks real is interesting to me. It catches me.” Martinez enthuses. “I was never a big fan of abstract work until I went to school (he laughs), since it’s a conceptual art school. I always thought abstract art was something anybody could do, but even if it does look that way it’s all in how you express yourself. By the way you use a brushstroke or something. There’s something intriguing about that. I don’t feel I need to choose one or the other (representational vs. abstract). I primarily started painting and drawing realistically and I figure that’s a skill I can incorporate, also, with something abstract.”

To contact Bob Eckert for assignments, consultations or workshops, please email [email protected]

or use the contact form on the About page

or use the contact form on the About page