Landscape Photographs

Story and photos by Bob Eckert

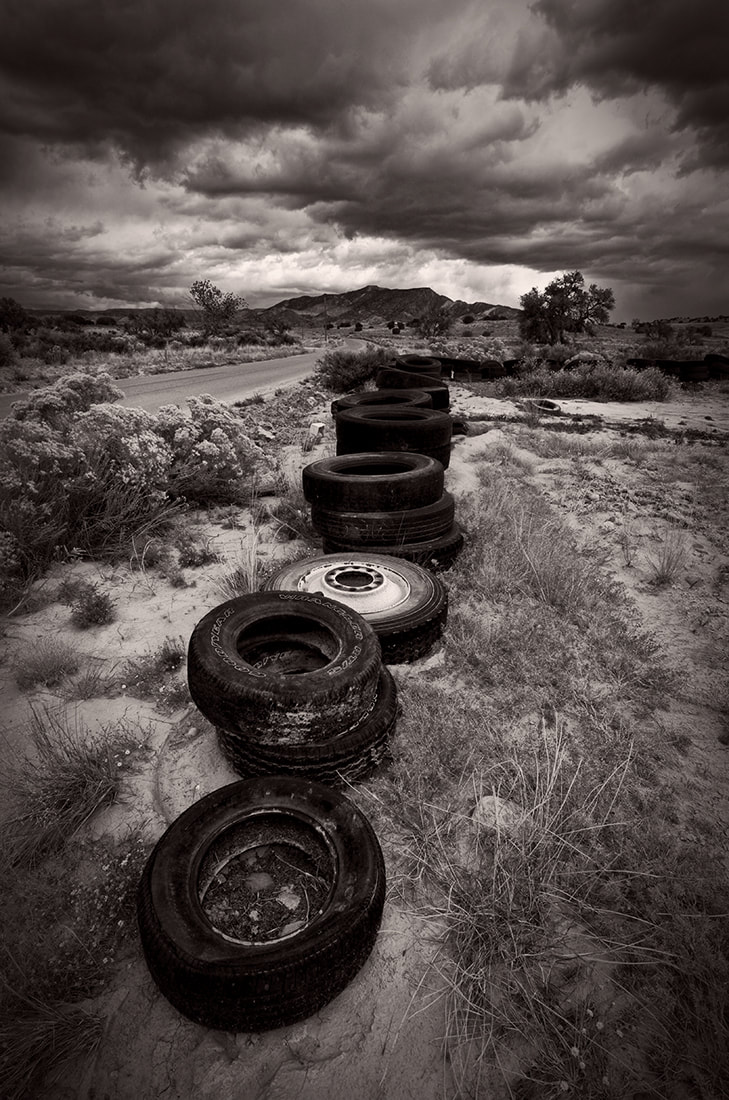

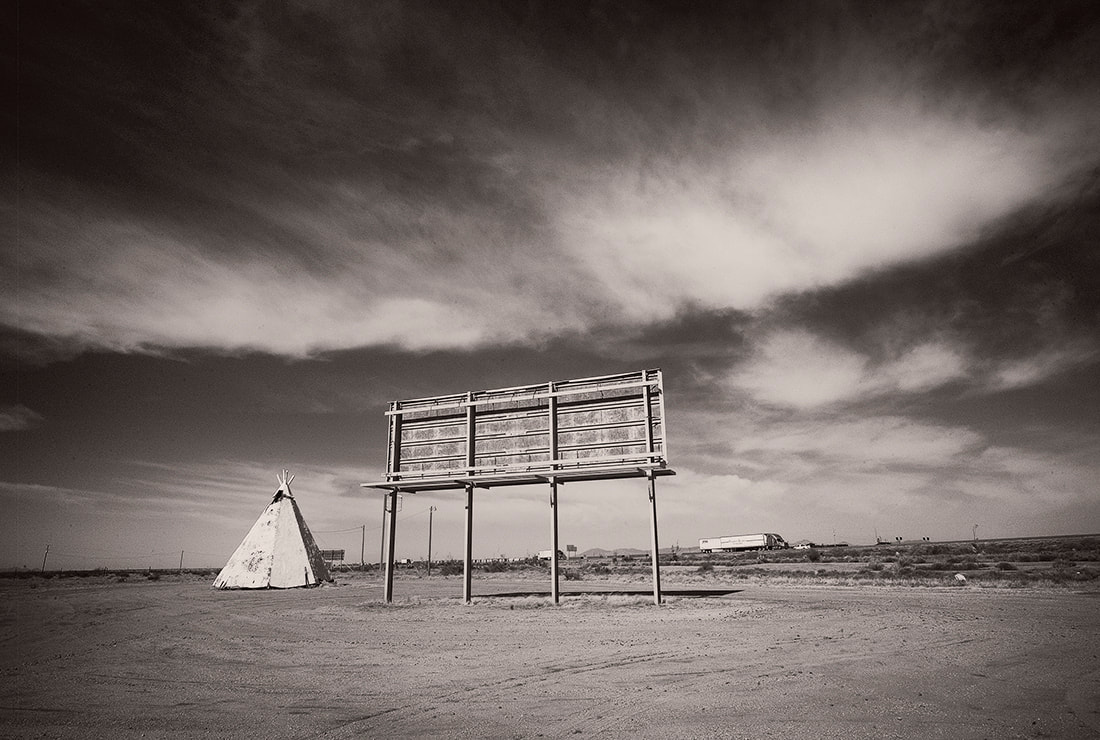

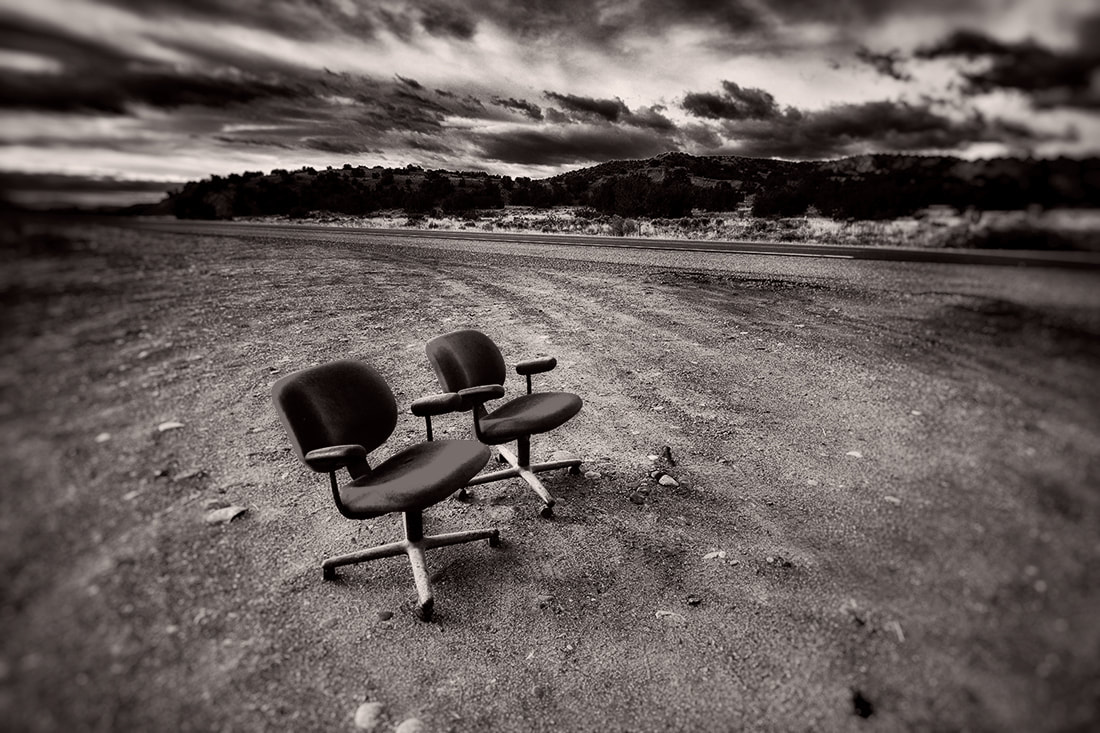

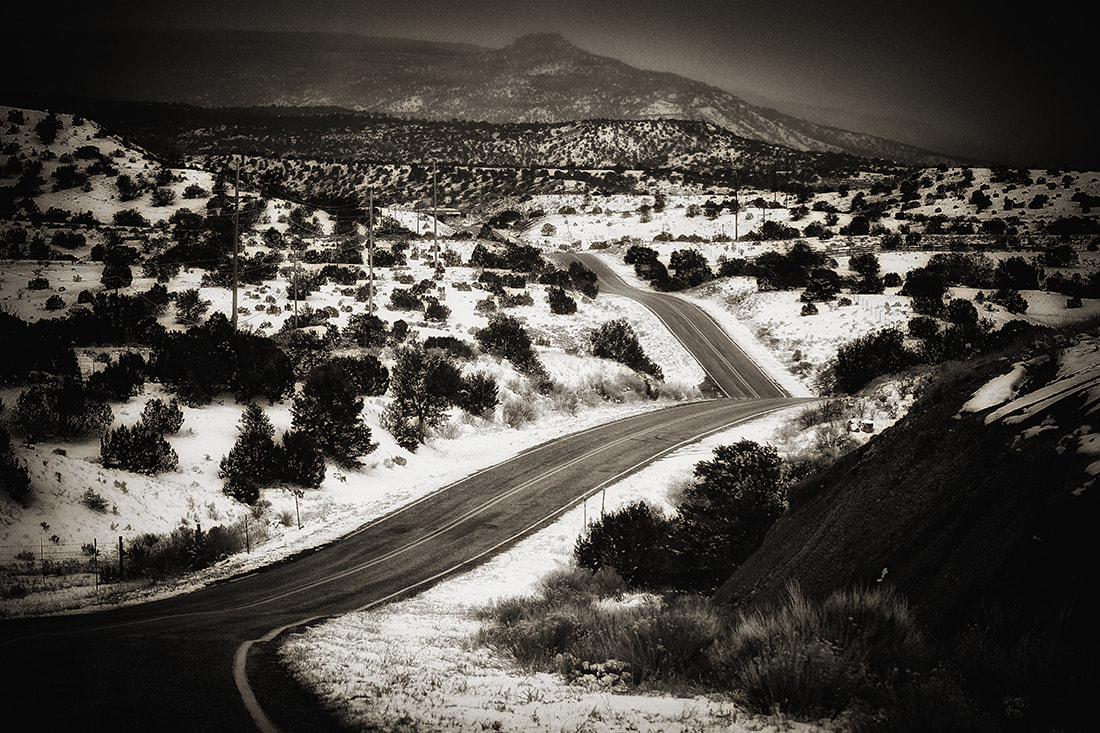

Although a lot of my landscape photography would be considered “traditional," the subjects I find most alluring are ones in which man’s hand on the environment is evidenced. I refer to the series as "Anti-Landscape Landscapes." The images might fall into the category of New Topographics, whose name came from an exhibit which opened in 1975.

I wasn’t aware of the “New Topographics” exhibit until years after it ended, but I realized I had a strong connection to the style and content of the work.

“New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape" was an exhibition that epitomized a key moment in American landscape photography. It was curated by William Jenkins at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House (Rochester, New York) in January 1975.

The exhibition had a ripple effect on the whole medium and genre, not only in the United States, but in Europe, too, where generations of landscape photographers emulated and are still emulating the spirit and aesthetics of the exhibition. Since 1975 "New Topographics" photographers such as Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Frank Gohlke and Stephen Shore have influenced photographic practices regarding landscape around the world. Moreover, and as a proof of the impact of this exhibition beyond the American scene, three out of the ten photographers in the show were later commissioned by the French government for the Mission de la DATAR, namely Baltz, Gohlke and Shore.

In addition to the eight then-young American photographers, Jenkins also invited the German couple, Bernd and Hilla Becher, then teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Germany). Since the late 1950s they had been photographing various obsolete structures, mainly post-industrial carcasses or carcasses-to-be, in Europe and America. They first exhibited them in series, as "typologies,” often shown in grids, under the title of "Anonymous Sculptures." They were soon adopted by the Conceptual Art movement.

Each photographer in the New Topographics exhibition was represented by 10 prints. All but Stephen Shore worked in black and white.

In his introduction to the catalogue, Jenkins defined the common denominator of the show as "a problem of style:" "stylistic anonymity,” an alleged absence of style. Jenkins mentioned Edward Ruscha's work, especially the numerous artist books (“26 Gasoline Stations” (1962), “Various Small Fires” (1964), “34 Parking Lots” (1967), and others) that he self-published in the 1960s as one of the inspirations for the exhibition and the photographers it features (except for the Bechers).

"The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion.”

I suppose, as it’s said, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Although a highway construction directional sign in the middle of the road, set against a backdrop of beautiful Southwestern plateaus isn’t necessarily considered beautiful, I do find it illustrative of man’s intrusion upon a lovely landscape — and the landscape, albeit with the intrusion of the highway and construction sign, is beautiful nevertheless.

It’s that combination of natural beauty and man’s intrusion that draws me. Do they “Eschew entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion,” as curator Jenkins stated, I think not.

Although a lot of my landscape photography would be considered “traditional," the subjects I find most alluring are ones in which man’s hand on the environment is evidenced. I refer to the series as "Anti-Landscape Landscapes." The images might fall into the category of New Topographics, whose name came from an exhibit which opened in 1975.

I wasn’t aware of the “New Topographics” exhibit until years after it ended, but I realized I had a strong connection to the style and content of the work.

“New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape" was an exhibition that epitomized a key moment in American landscape photography. It was curated by William Jenkins at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House (Rochester, New York) in January 1975.

The exhibition had a ripple effect on the whole medium and genre, not only in the United States, but in Europe, too, where generations of landscape photographers emulated and are still emulating the spirit and aesthetics of the exhibition. Since 1975 "New Topographics" photographers such as Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Frank Gohlke and Stephen Shore have influenced photographic practices regarding landscape around the world. Moreover, and as a proof of the impact of this exhibition beyond the American scene, three out of the ten photographers in the show were later commissioned by the French government for the Mission de la DATAR, namely Baltz, Gohlke and Shore.

In addition to the eight then-young American photographers, Jenkins also invited the German couple, Bernd and Hilla Becher, then teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Germany). Since the late 1950s they had been photographing various obsolete structures, mainly post-industrial carcasses or carcasses-to-be, in Europe and America. They first exhibited them in series, as "typologies,” often shown in grids, under the title of "Anonymous Sculptures." They were soon adopted by the Conceptual Art movement.

Each photographer in the New Topographics exhibition was represented by 10 prints. All but Stephen Shore worked in black and white.

In his introduction to the catalogue, Jenkins defined the common denominator of the show as "a problem of style:" "stylistic anonymity,” an alleged absence of style. Jenkins mentioned Edward Ruscha's work, especially the numerous artist books (“26 Gasoline Stations” (1962), “Various Small Fires” (1964), “34 Parking Lots” (1967), and others) that he self-published in the 1960s as one of the inspirations for the exhibition and the photographers it features (except for the Bechers).

"The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion.”

I suppose, as it’s said, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Although a highway construction directional sign in the middle of the road, set against a backdrop of beautiful Southwestern plateaus isn’t necessarily considered beautiful, I do find it illustrative of man’s intrusion upon a lovely landscape — and the landscape, albeit with the intrusion of the highway and construction sign, is beautiful nevertheless.

It’s that combination of natural beauty and man’s intrusion that draws me. Do they “Eschew entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion,” as curator Jenkins stated, I think not.

To contact Bob Eckert for assignments, consultations or workshops, please email [email protected]

or use the contact form on the About page

or use the contact form on the About page